The law on DEI hasn’t changed

A civil rights attorney on risk, backlash and what’s legal

Few areas of law are shifting as quickly, or as publicly, as diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI). In the wake of recent affirmative-action rulings and a growing wave of DEI-related litigation, lawyers across practice areas are being forced to rethink how policy, compliance and advocacy intersect. To help make sense of where the law is headed,

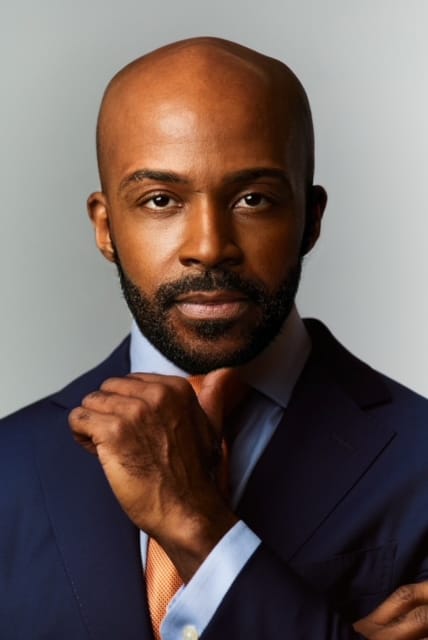

Raise the Bar spoke with Alphonso David, Civil Rights Attorney, co-counsel to the Fearless Fund, and president and CEO of the Global Black Economic Forum.

—Interview by Emily Kelchen, edited by Bianca Prieto

Your career spans litigation, government policy and organizational leadership. What lessons have you learned about balancing legal risk, public perception and the pursuit of justice?

One of the most important lessons I have learned is that legal risk, public perception and justice are often discussed as if they are in tension, when in reality they are deeply connected. The greatest risk usually comes from misunderstanding the law, not from advancing diversity, equity and inclusion.

Too often, institutions allow fear-driven narratives to shape decisions, instead of grounding themselves in statutory obligations, data, precedent and their inherent values. In areas such as diversity, equity and inclusion, silence or retreat is often framed as the “safe” option. It is not.

When organizations abandon lawful, evidence-based practices because of perceived cultural backlash, they create reputational harm, operational instability and in many cases greater exposure to liability under civil rights laws.

Justice requires clarity and discipline: knowing what the law actually requires, communicating that clearly to stakeholders and refusing to confuse political noise with legal reality.

Public perception matters, but it cannot be managed through capitulation. It must be managed through transparency—explaining why programs exist, what problems those programs are addressing and how those programs align with both the law and the organization’s mission. Institutions that navigate this moment best are those that lead with facts, values and consistency rather than fear.

You say the greatest risk comes from misunderstanding the law. What are the most significant misconceptions about diversity, equity and inclusion and affirmative action initiatives?

The most persistent misconception is that diversity, equity and inclusion programs and affirmative action initiatives are the same, which they are not. They are predicated on distinct legal doctrines. Further, there is a binding nationwide court ruling on affirmative action in the education context, but there is no such ruling on diversity, equity and inclusion programs and yet each day some institutions are changing practices, as if the law on diversity has changed. It has not.

Another persistent misconception is that both diversity programming and affirmative action are about preferences or quotas rather than remedies. Quotas have been illegal for decades. What remains lawful—and necessary—are targeted, data-driven efforts designed to correct documented exclusion and market failure.

Further, some assume that diversity programs exist outside of traditional civil rights frameworks. In reality, diversity programs were created in response to the civil rights laws of the 1960s to ensure compliance. These programs are grounded in the same legal principles that govern fair lending, fair housing, employment discrimination and government contracting.

Courts and legislators sometimes lose sight of that continuity and instead treat diversity, equity and inclusion as a novel or suspect concept, when it is simply a modern application of long-standing law.

So you think lawyers need to re-frame these issues?

For lawyers, framing is critical. These cases should not be argued as culture-war disputes. They should be argued as economic and legal questions. What is the documented disparity? What evidence shows the market has failed to correct it? How narrowly tailored is the program to address that failure?

When framed around outcomes, data and statutory purpose rather than abstract rhetoric, these issues become much harder to disregard or mischaracterize.

It’s also worth exploring the growing disconnect between shareholder sentiment, consumer expectations and the legal advice many organizations are receiving about diversity, equity and inclusion. Lawyers have a critical role to play in closing that gap by grounding counsel in law, data and long-term risk rather than short-term political pressure.

I would recommend that readers review the Questions to Ask Diversity Deniers Handout that we created at the Global Black Economic Forum last year.

What strategic shifts should advocates and in-house counsel consider when defending or designing diversity, equity and inclusion programs to withstand heightened scrutiny?

As a threshold matter, lawyers should not conflate risk and law. The laws that undergird diversity programs have not changed; the political environment has changed. Further, lawyers should not conflate the Supreme Court affirmative action decision in the education context with diversity, equity and inclusion programs in private contracting, grantmaking or employment.

The Fourteenth Amendment does not apply to private companies (absent government action), and it is Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 that covers employment, not Title VI (education programs receiving federal assistance), which was the subject of the Court’s affirmative action decision. There are different legal frameworks, case law and agency guidance that govern federal funding of education programs vs. private employment, contracting or grantmaking.

As it relates to diversity, equity and inclusion programs, institutions should be focused on precision, not abandonment. Diversity programs must be rooted in clearly articulated objectives, supported by data and tied directly to identified barriers or disparities. Counsel should ensure there is a strong evidentiary record explaining why a program exists and how it operates.

One strategic shift is moving away from broad or symbolic language and toward function-based design. Focus on access, outreach, pipeline development and removing structural barriers—areas that are both legally defensible and operationally effective. Another is regular program auditing, ensuring initiatives remain narrowly tailored, compliant with evolving case law and aligned with organizational goals.

For in-house counsel and mid-size firms in particular, the key is integration. Diversity, equity and inclusion cannot be siloed as a values initiative separate from compliance, risk management or growth strategy. When equity programs are embedded into core operations—such as talent development, procurement and market expansion—they are easier to defend because they are demonstrably tied to performance, fairness and legal obligations.

You're all caught up!

Thanks for reading today's edition! You can reach the newsletter team at raisethebar@mynewsletter.co. We enjoy hearing from you.

Interested in advertising? Email us at newslettersales@mvfglobal.com

Was this email forwarded to you? Sign up here to get this newsletter every week.

Raise the Bar is written and curated by Emily Kelchen and edited by Bianca Prieto.

Comments ()